Marta Astfalck-Vietz (German, 1901-1994), Untitled, 1927, Berlinische Galerie - Landesmuseum fur Moderne Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur. This is a self-portrait which, according to the label, "reveals her exploration of masquerade and the increased personal and sexual freedom experienced by growing numbers of women during the 1920s."

I must stop researching and writing about the show and its photographers or I'll still be writing long after the pictures come down (which is January 30!).

The more I learn about the photographers, the more I want to learn and return to see their works and read their biographies and find out more about their enticing, engrossing lives and shout: "Right on, sisters!"

It was 100 years ago when this period of photographs began, when the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed, granting women the right to vote in the U.S. (about 25 years after the UK extended the right, and almost 200 years following Sweden's right to vote which was granted female property owners).

"Right on, sisters!"

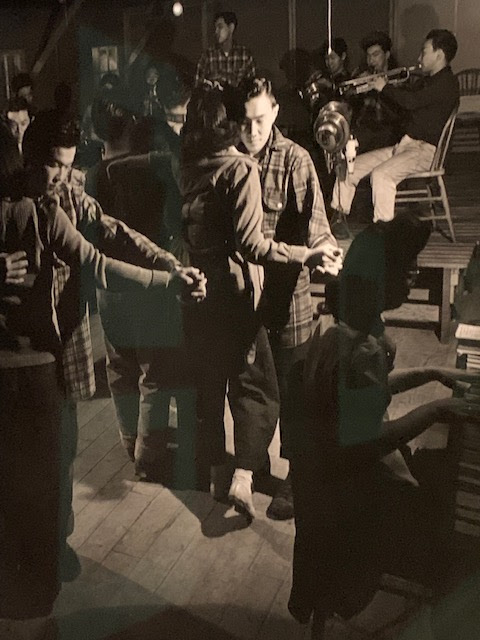

Look at the independence, the strength, the drive in these pictures, some of my favorites which I have included here. The images are stunning and you will remember some long after you have left the show.

They are not happy pictures: They are telling, historical; they portray the times, presenting society of the era and place, realistic, stark in many cases, representing hundreds of observances of world events, of everyday lives.

The portraits excel about the time when the "new woman" was emerging to assume independence and rights, values we still strive to reach today.

Almost 50 lenders, including Sir Elton John and the California African-American Museum, loaned pictures.

An excellent catalog includes almost 300 pages of mostly black and white pictures, some spread over two facing pages, with enlightening brief biographies of most of the photographers.

Thank you, National Gallery of Art and sponsors, the Robert and Mercedes Eichholz Foundation, Trellis Fund, Exhibition Circle of the National Gallery of Art and the Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation for another spectacular show which gives me confidence to walk another mile. "That's what art can do!"

The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and curated by Andrea Nelson, associate curator in the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art.

Also, upcoming this week is a free two-day virtual symposium, "Global Perspectives on The New Woman Behind the Camera," Jan. 19-20, 2022, featuring talks by historians, curators, and artists, made possible by the James D. and Kathryn K. Steele Fund for Photography. Register here.

What: The New Woman Behind the Camera

When: Now through Jan. 30, 2022, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., every day

Masks: Required of all visitors, ages 2 and above, despite vaccinations.

Metro stations for the National Gallery of Art:

Smithsonian, Federal Triangle, Navy Memorial-Archives, or L'Enfant Plaza

For more information: (202) 737-4215

patricialesli@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment